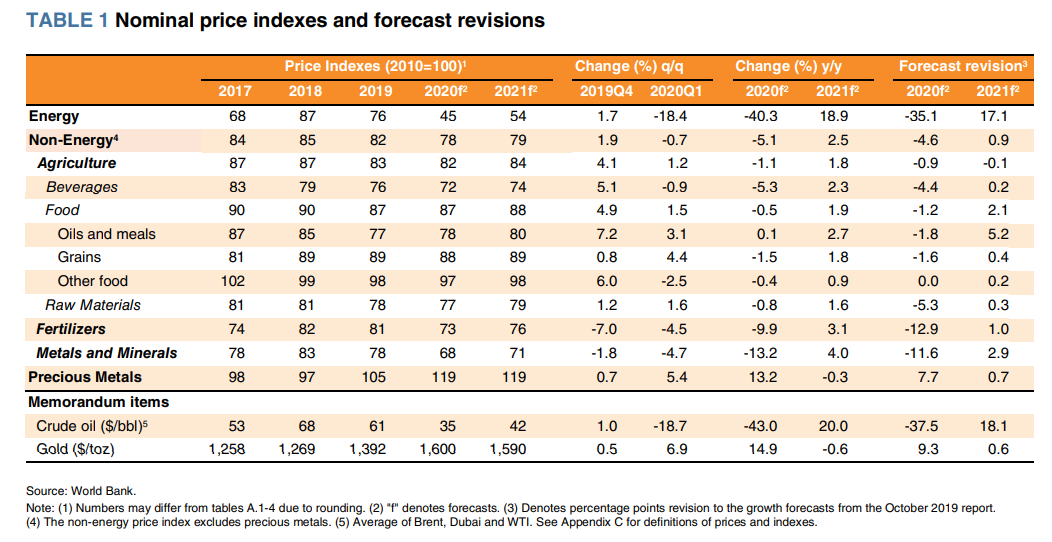

Almost all commodity prices saw sharp declines during the past three months as the COVID-19 pandemic worsened. Mitigation measures have significantly reduced transport, causing an unprecedented decline in demand for oil, while weaker economic growth will further reduce overall commodity demand. Crude oil prices are expected to average $35/bbl this year and $42/bbl in 2021—a sharp downward revision from October in both years. Non-energy prices are also expected to fall this year. Metals are projected to decline more than 13 percent in 2020, before recovering in 2021 while food prices are expected to be broadly stable. The risks to the price forecasts are large in both directions and depend on the speed at which the pandemic is contained and mitigation measures are lifted. A Special Focus investigates the impact of COVID-19 on commodity markets and compares it with previous disruption episodes. It finds that the impact of COVID-19 has already been larger than most previous events and may lead to long-term shifts in global commodity demand and supply. A Box examines the impact of international commodity production agreements, with a particular focus on OPEC, and concludes that OPEC+, the last remaining international agreement to manage supply, is subject to the same forces that led to the collapse of its predecessors.

Recent trends

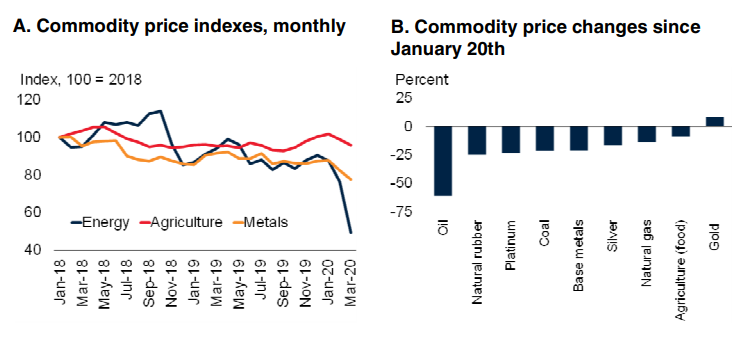

Commodity markets have been buffeted by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has already caused a historical sudden stop in economic activity (Special Focus). The pandemic has affected both the demand and supply of commodities through the impact of mitigation measures on activity and supply chains. The prices of most commodities have fallen since January, especially those that are related to the transportation industry (Figure 1.A, Figure 1.B). Energy prices fell 18.4 percent (q/q) in 2020 Q1, with a marked deterioration throughout the quarter as the severity of COVID-19 became increasingly apparent. Crude oil prices averaged $32/bbl in March, a decline of 50 percent compared with January. Prices reached a historic low in April with some benchmarks trading at negative levels. Demand for oil has collapsed as a result of COVID-19 mitigation measures which have sharply curtailed travel and transport, which account for around two-thirds of oil demand. The fall in prices was exacerbated by the breakdown of the production agreement between OPEC and its partners in early March, and prices failed to rally when a new agreement to reduce production by 9.7mb/d disappointed markets in April (Box, Energy section). While natural gas prices have also seen sizeable declines, albeit less than for crude oil, coal prices have seen smaller declines partly because demand for heating and electricity has been somewhat less affected by mitigation measures. Most non-energy prices also fell in 2020 Q1, but by less than energy prices. The metals and minerals price index fell 5 percent on the quarter, but with significant variation among its components. Copper and zinc prices declined by around 15 percent relative to their January peak, reflecting their close relationship with global economic activity. In contrast, iron ore prices have fallen just 7 percent, with weakening demand partly balanced by supply disruptions. Among precious metals, gold prices rose modestly amid heightened uncertainty and safe-haven flows, while platinum prices dropped by 23 percent reflecting their heavy use in the production of catalytic converters in the transportation industry. With some exceptions, agricultural commodity prices saw minor declines during the first quarter reflecting their indirect relationship to economic growth. However, natural rubber prices fell 25 percent from their January peak largely because two-thirds of the crop is used in the manufacture of tires. Prices of maize and some edible oils fell as well due to the collapse of biofuel demand.

FIGURE 1 Commodity market developments

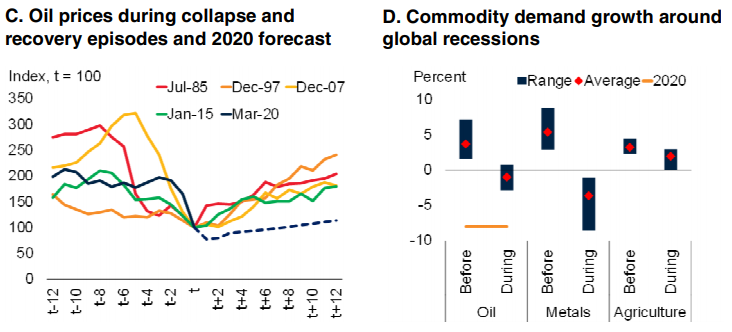

COVID-19 caused widespread declines in commodity prices in February and March, with energy the most affected. Oil prices have been hit by a plunge in transport, weaker economic growth despite cuts by OPEC and its partners. Oil prices are forecast to average $35/bbl in 2020, which would be the weakest price recovery in history, reflecting the unprecedented collapse in oil demand expected this year.

Source: Bloomberg; BP Statistical Review; IEA; USDA; World Bank; World Bureau of Metal Statistics A. Last observation is March 2020. B. Last observation is April 17 2020. C. Lines indicate oil prices for 12 months before and after the trough (t) of major price collapses, indexed to 100 at the trough (t). Dashed line indicates forecast for 2020. D. Dates of recessions taken from Kose, Sugawara, and Terrones (2020). Four recessions are included: 1974-75; 1981-82; 1990-91; and 2008-09. "Before" shows average annual growth rates in commodity consumption over the three years before the recession. "During" shows average annual growth rates of recession years. note that in 1980 a global slowdown occurred with similar negative growth rates in consumption; as such the "Before" period covers 1977-79. 2020 line shows the IEA’s forecast for oil demand growth in 2020. Demand forecasts are not available for metals and agriculture.

Outlook and risks

Energy prices are expected to average 40 percent lower in 2020 than in 2019 (a major downward revision from October) but see a sizeable rebound in 2021 (Table 1). Non-energy prices are projected to decline 5 percent in 2020 (a smaller downward revision from October) and stabilize in 2021. The outlook is exceptionally uncertain and depends on the duration and severity of the pandemic, and how quickly mitigation measures can be lifted. Oil prices are projected to average $35/bbl in 2020 before recovering to $42/bbl in 2021, substantially lower than the October forecast of $58/bbl and $59/bbl. Oil prices are expected to recover only very gradually from their current low levels, before picking up more strongly into next year, which would be among the weakest recovery from a price collapse in history (Figure 1.C). The forecast reflects an expected plunge in oil demand of almost 10 percent (9.3mb/d), which would be unprecedented in history. The largest prior decline was in 1980 when oil demand fell by 4 percent (Figure 1.D). Against this drop, the production cuts by OPEC and its partners may be insufficient, with a major surplus expected in 2020Q2, which will likely overwhelm storage capacity and cause widespread shutdowns of production among other producers, particularly in the U.S. and Canada. Prices are expected to rise in 2021 as demand recovers, albeit to a lower level than previously forecast. Risks are predominately to the downside and include a slower end to the pandemic that could lead to much lower demand than currently forecast, as well as a deeper-thanexpected recession. To the upside, a faster fall in production could cause oil prices to rise more sharply in the latter half of 2020 and into 2021. Metal prices are projected to fall 13 percent in 2020 before rebounding modestly in 2021, as slowing global demand and the shutdown of key industries weigh heavily on the market. Risks to this outlook are to the downside, including a greater-than-expected slowdown in global growth. Agricultural prices are expected to remain broadly stable in 2020 as they are less sensitive to economic activity than industrial commodities, while production levels and stocks for most staple foods are at all-time highs. However, concerns about food security remain. Some countries have already announced temporary trade restrictions such as export bans, while others began stockpiling food commodities through accelerated imports. Although these measures have not yet been used widely, they could lead to problems if they are used extensively. Also, there may be problems with food availability (and price spikes) at the local level due to supply chain disruptions and border closures in response to containment strategies, that may restrict food flows or movement of labor. This edition of the Commodity Markets Outlook features a Special Focus on the implications of COVID-19 for commodity markets, and a Box on the impact of commodity production agreements, with a particular focus on OPEC.

Special focus: A shock like no other: The implications of COVID-19 for commodity markets

The outbreak of COVID-19 has been accompanied by widespread declines in commodity prices. The combination of both major demand and supply shocks occurring simultaneously is unprecedented among previous events. The mitigation measures taken to control the spread of the virus have resulted in an unprecedented collapse in oil demand and the steepest one-month decline in oil prices on record. In the short-run, in addition to weaker demand, disruptions to supply chains could cause dislocations in the consumption and production of other commodities and imperil food security. In the longer-term, the pandemic could have lasting impacts on commodity demand and supply, affecting both commodity exporters and importers. A shift toward remote working may reduce travel and hence demand for oil, while a preference for near-shoring and the retrenchment of global value chains could cause a persistent shift in the configuration of supply chains and associated commodity demand. Policymakers in both commodity-exporting and commodityimporting emerging and developing economies should take advantage of these shifts to reduce commodity market distortions. This is particularly true for energy markets, and the plunge in oil prices is an opportunity to eliminate subsidies.

Box: Set up to fail?

The inevitable collapse of commodity agreements OPEC+ is the only surviving internationally coordinated effort to manage commodity supplies. Previous efforts since World War II, including agreements for tin, coffee, and rubber production, have all collapsed. Commodity production agreements tend to sow the seed of their own collapse, by keeping prices artificially high, which in turn encourages new producers to enter the market, as well as inducing innovation and substitution. The economic forces created by supply management of the oil market since 1985 resemble those observed in these previous coordination efforts. While OPEC and its partners agreed to new production cuts in April, in the longer term, the current arrangement will most likely be subjected to the same forces that led to the collapse of its predecessors.

Source: worldbank.org